On a sunny Friday afternoon on the first of August, Pinocchio and Jiminy Cricket’s ‘Always Let Conscience Be Your Guide’ played on the screens of Mahatma Hall to begin the most interesting HS workshop I’d attended in three years. This was followed by Eminem’s ‘Guilty Conscience’ which sufficed to wake us up from our post-lunch slumber. The facilitator was Anmol Tikoo, a filmmaker and an educator of philosophy, and he was all set to speak ‘conscience’ with us.

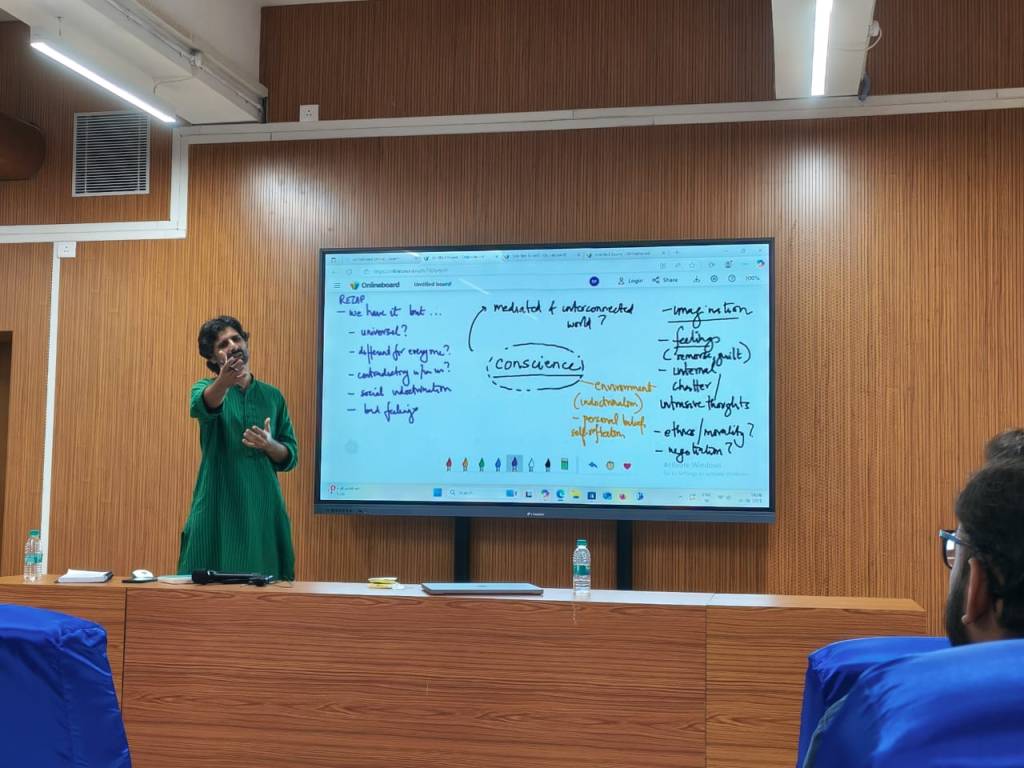

He threw a softball to start us off and establish common ground: Do you’ve a conscience? Do you think others have a conscience? We universally responded in the affirmative. How many of you think there’s a crisis in conscience today? Approximately half the hands went up, contending that though it has always been hard to live in line with one’s conscience, it has become particularly hard to do so in today’s world. We proposed a plethora of reasons as to why. The anomie could be an inevitable result of urban construct and individualism that breeds selfishness cleverly couched as self-preservation. The comfort of instant gratification is an easier choice to favour than standing against the social pressures of negative sanctions for acting conscientiously. It doesn’t help that there’s no reward for conscience which is becoming increasingly associated with a notion of thankless sacrifice. An interconnected world also offers us the convenience of mediating violence through others, where we rest easy adopting the ‘neutral’ facade of silent conduits than active perpetrators.

Are there stupid questions? I nodded smilingly and he challenged me to give an example. “I’ll point it out when someone asks one,” I quipped jokingly to soft laughter. Mr Tikoo declared that, in fact, there were no stupid questions though not all questions were made equal. There were basic questions of fact (What?), knowledge (How?) and understanding (Why?) and then complicated ‘should’ questions that deal with values. You can answer ‘should’ questions through conscience, acting from the oft-quoted adage ‘Do unto others as you will have done unto you.’ These questions incite a negotiation through internal chatter, intrusive thoughts and feelings pertaining to how we construct ethics and morality. Acknowledging conscience as a ‘site of negotiation’ also urges us to embrace its ever-evolving nature and helps us reconcile that it can be both universal and contextually tied to a time and place, which brings us to the next important question.

What is the origin of conscience? Is it merely a social construct? A few of us argued that the early whispers of conscience stemmed from the environment, from authoritative or utilitarian values of family, community and religion that informed groupthink but all of us concurred that the individual had a say. Conscience is more than the ‘voice of society’ within us. It is mixed with personal belief and evolves with self-reflection as we process new experiences. We cannot argue that it is purely individual for that would be a conversation stopper, prompting everyone to ‘live and let live’ without any global or majority resolution of moral dilemmas. Nor can we argue that it is purely social because that would undermine our autonomy in dealing with morality which no one has a monopoly on. This liberty is fundamental in the modern world to challenge and refine epistemic and ideological compasses that inform our ethical discourse within and with one another. This trade-off between a collective conception and an individual negotiation also helps us accommodate and engage with the multiple consciences we may harbour.

Sketch pens and chart paper were now in order to conjure up our individual images of conscience- the words, stories and feelings we associated with it. This evoked tales, symbols and emotions that helped us confront many interesting questions: What is conscience to you? Do you feel the pangs of ‘bad conscience’ more than the pats of ‘good conscience’? Should the world get rid of conscience? But, that’s a compelling story for next time.

(Stay tuned for part 2)