If you happen to walk through the streets of Chennai, late-evening on a weekday, I am reasonably certain you will meet hundreds of people who look exactly like my father. Formal blue-shirts, receding hairlines, restive in their little cars with eyes on the traffic jam ahead. Thousands of board meetings, sales graphs, packed lunches, and caffeine looking to go home after a long day. They could be stuck there for hours, but it is only very rarely that someone would flip out and start screaming. The rest of them watched that in silence and hidden amusement. No different from them all, my father, or Appa as I call him, lived his entire life by the law of inertia. He had set into the monotony of traffic jams, blue shirts, and the occasional road rage so well that you would not imagine him any other way. One rarely saw his eyes sparkle while talking about himself. He hardly had any friends. His whole life revolved around my mother, my sister, and me. On one of those rare days, he spoke about his boyhood, I find myself wondering what my father wanted to be at that point. After all, being a human resources manager for a corporate company is no one’s dream. Yet in the course of life, every other person in every other traffic signal in my city or otherwise worked jobs that were starkly similar to his. Appa always took the path of least resistance; he let inertia carry him to his college, career, marriage, children, and everything that came with it. I frowned upon this constantly as I find mediocrity very unsettling. The struggle of being in between the frontrunners and the underdogs makes me impatient and irritable. It was like waiting in a queue, constantly weighing whether to wait for your turn or forego your own efforts and leave. When someone has lived in mediocrity his whole life, one would at least expect him to complain about it. Yet every time I look at him, there was this annoying calm on his face, a feeling of complacency which made me vow to never be like him.

He blissfully spent most of his time putting out fires and crossing bridges only when we got to it. However, a parent of two girls inevitably has to make a call to choose between what keeps them happy or what keeps them safe. If there was one thing, I have seen Appa passionate about, it was the choice to always choose the latter.

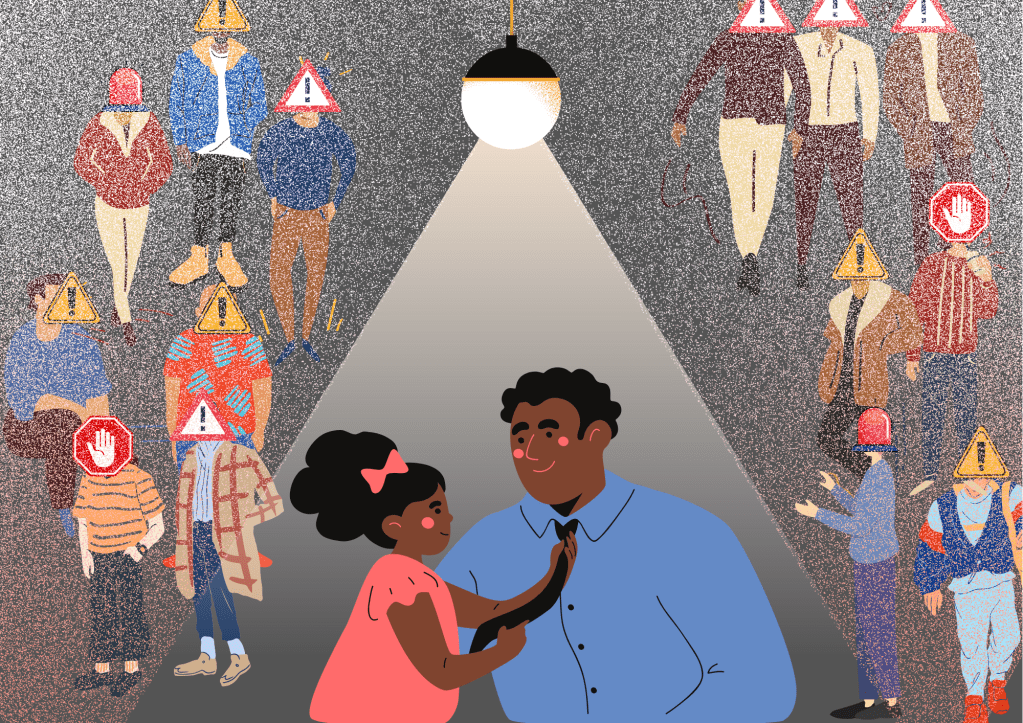

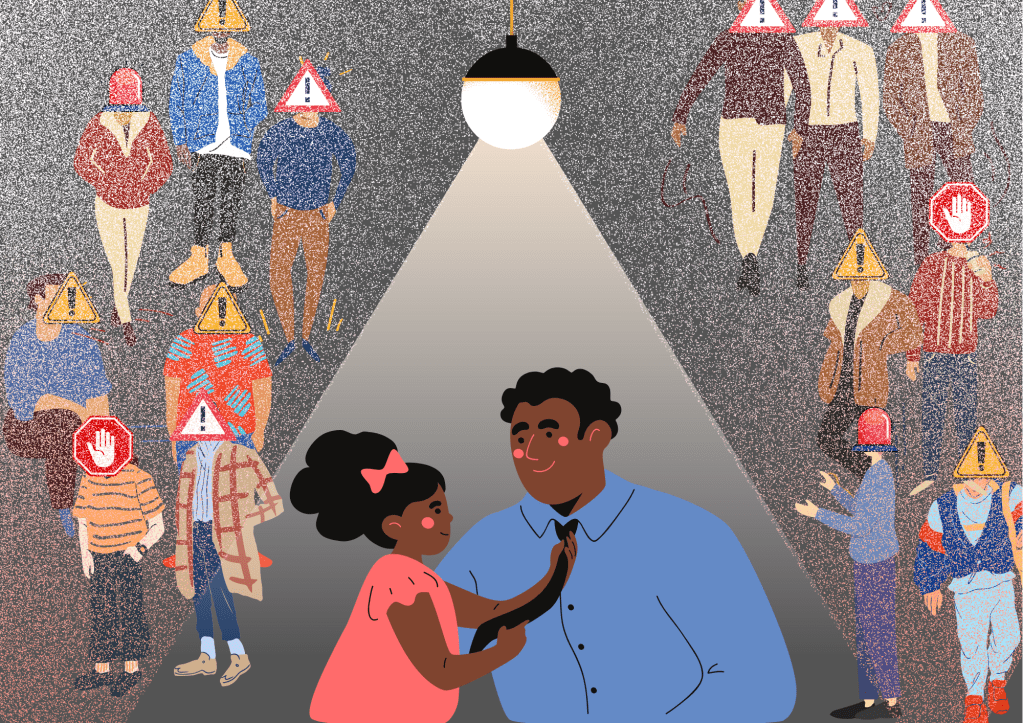

The signs were everywhere, and he never tried to hide them anyways. When television first came home and romantic songs played on, he made up alternate jargon lyrics to prevent us from learning what the actual lyrics meant. I still remember his lyrics better than the original ones. He never questioned my career choices, except when he told me I could be anything but a model, actor, or police officer. None of those interested me anyway, so I nodded silently. He vehemently believed that any person involved with movie making was always waiting to catfish teenage girls the first chance they got. Appa was convinced that every lyric was suggestive; every movie showed women in poor light to an extent where he would discover double entendre in dialogues that weren’t even meant to be that way. There is this popular family anecdote about how a director approached my school asking for child actors to play a small role in a multi-star movie. The moment he heard this, he rushed from work and picked me up from school midway, even though I wasn’t even being considered for the part. And then there was a time when a struggling actor moved in downstairs, and Appa did everything in his power to evict him as soon as possible, even if it involved shady allegations. My first Facebook account was a secret; he still disapproves of me taking pictures for social media. Every time I go out with him, he becomes a hound dog scouting the street for anyone who could possibly be a sexual predator. He stares at those who stare at me while asking me to keep my eyes firmly to the ground. There was a time when I was groped on the street, but I never mentioned it to him out of the fear that he would take away the little independence I had. On those days, when I let out a sigh of relief every time I reach home safely, I get where Appa is coming from.

I distinctly remember the day I got my own room at home. It had a balcony that opened out into the streets but high enough that one had to really squat and roll on the road to even sneak a peek into my room. When I was asleep, he pasted newspapers on the windows and secured them with duct tape. Apart from looking distasteful, it was a constant reminder that I needed to be protected from the male gaze. The curious fact remains that he never did these from a place of authority; one could see him tremble with fear every time I was catcalled on the road. For someone who remains neutral through most things in life, I saw him cry when I told him a boy slapped me at school. He didn’t get angry, he just got sadder, and it was very unclear why.

For years I continued to be under the impression that he was the opposite of everything I stood for. When I moved out, I kept telling myself that I will be free to do what I want; I may even act in a movie or two. When that day finally arrived, I found a fear within myself that never existed before. I began keeping my eyes down and layering up my clothes even when he wasn’t around to rebuke me. I constantly checked for open windows every time I had to change my clothes. Over time, I realized that I used to walk bravely, not because I wasn’t scared, but because someone else bore the fear for me, someone else exerted vigil on my behalf. My safety net was torn, and every time I was being ogled at, I choose flight over fight, just like Appa would.

We are always under the misapprehension that feminism is heroic; it is a story of courage and the sound of broken glass ceilings. Curfews, dress codes, and running away from moviemakers do not evoke feminism the way bra-burning or mob protests do. However, the fact remains that very often in this fight, we turn up with nothing. On some days , we give in. On some days, we fight back. It is not about the fight but about wanting to fight. It rests in our silent internal struggles, in the choices that we consciously make every time we put ourselves out in this world. And on most days, it doesn’t look heroic and you can’t hear the glass ceiling shatter. But the stones we throw, go closer and closer to the glass with every attempt. We await the day it falls. Much like the duct tape and newspaper that Appa stuck on my balcony window.