— Devika Deevasan

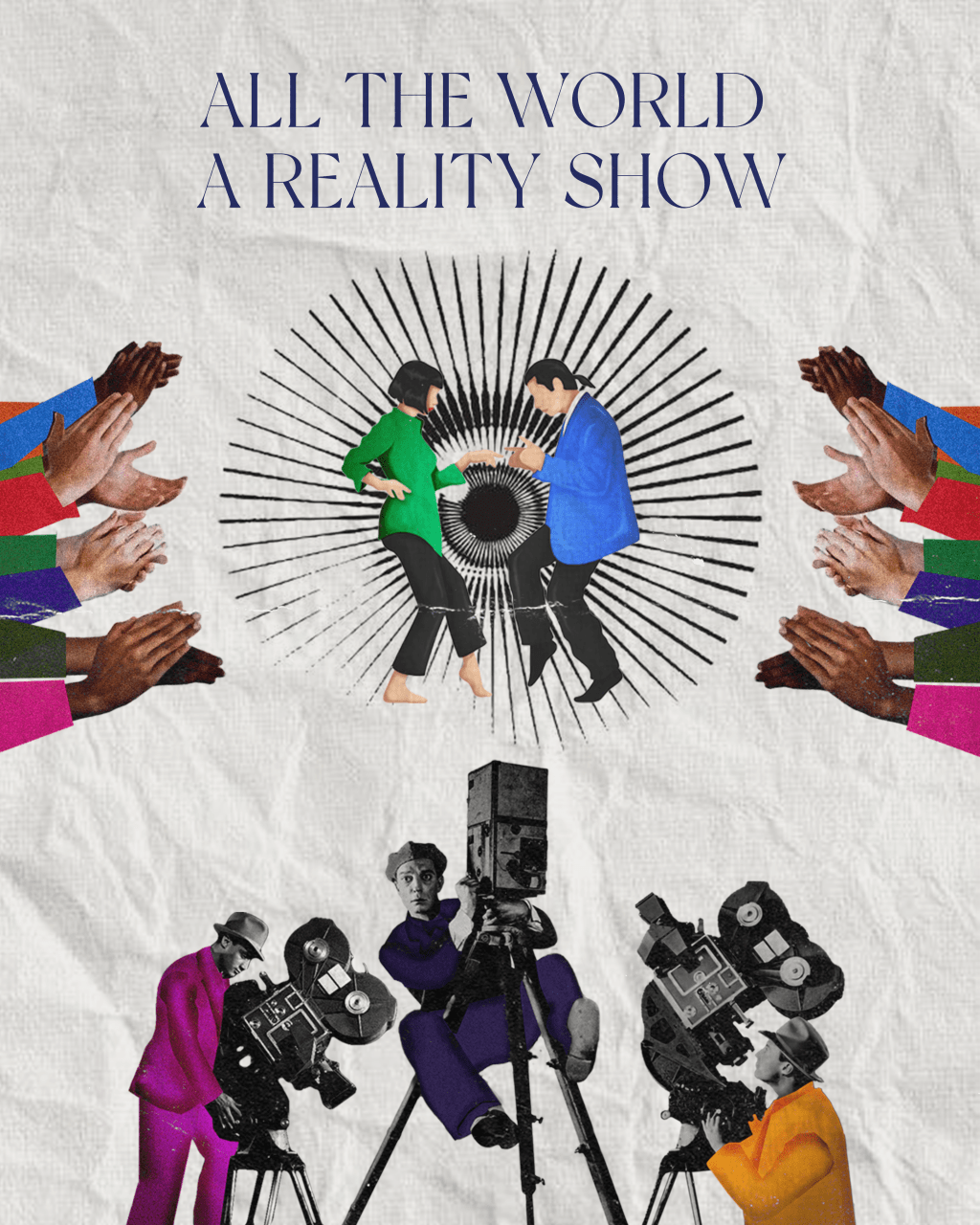

If you’re offered 1 million dollars to spend five months in a house with six strangers having your every action documented for the world to see, would you do it? Let’s take a look into the larger, invisible ramifications of agreeing to this hypothetical offer.

The first-ever ‘soap opera’ reality show, The Real World premiered in 1992 on MTV and revolved around 7-8 people confined to go about their lives with every move filmed on camera. Eight years later, along came Big Brother, jokingly (or maybe not so) named after the Orwellian authoritarian figure featuring the same name and having successful runs and remakes in multiple countries. With time, reality shows began to grow from being centred around ordinary people to depicting more unusual lives. The Simple Life featured rich socialites Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie attempting to do low-paying jobs. This was followed by the more successful multi-career starting family reality show, Keeping Up With the Kardashians. Alongside celebrity reality TV, dating shows like The Bachelor and Love Island began to gain popularity for coupling groups of attractive, single people in a deserted yet decadent mansion with the task of finding love. Reality TV began to branch out to include depictions of individuals in abnormal settings like getting stuck on a deserted island, surviving a night in a forest with no supplies, performing tasks, or getting through obstacle courses. The definition shifted from “reality” to more “unscripted”.

While these developments occurred, the audiences devoured these shows with much intensity. The popular shows generated widespread fanfare prompting showrunners to include the audience in decision-making. The contestants’ tenure in the show began to depend on their peers and the audience’s opinion of them. This move introduced a new tension to the fishbowl, with contestants having to be as authentic as possible while maintaining likeability. Viewers eagerly lapped up every moment of happiness, conflict, and drama that the producers injected into the show via unusual tasks and games that the contestants were asked to perform. Why are viewers so invested in the lives of other individuals? In every human, there exists some degree of “Schadenfreude”, the joy or pleasure that comes from witnessing the troubles or failures of others. Who knows? Maybe the urge comes from simple curiosity or pure salacious voyeurism. That discussion is for another time.

Regardless, there is an undeniable obsession that society has with everyone’s lives. With reality TV, not only does society get to openly gawk at the private lives of contestants (who did consent to it entering into the show), but they also get to comment on it. However, unlike in real life where one is protected to some degree from the constant critique of others, the contestants are always subject to opinions. With the growth of cancel culture, and the power and control of social media on the lives of people, the chances of simple disapproval and critique of a contestant leading to them facing severe repercussions like cyber bullying is much higher. An argument can be made that the contestants signing off on their privacy to a corporation in return for fifteen seconds of fame may not be fully aware of the magnitude of the implications of their actions.

While discussing surveillance as a student of Social Sciences, I cannot help but remember the panopticon. The institutional disciplinary concept involves a central observatory tower placed within a circle of cells, ensuring that the inmates of the cell are never truly aware of when and by whom they are being watched. Upon first glance, it might look like it’s easy to compare the Big Brother House or Love Island Villa to a panopticon. The miked contestants going about their days in the mansion bugged with cameras are aware, just like the prisoners in a panoptical institution, that their every action is being watched. However, according to Foucault, the panopticon was a measure to modify and self-police behaviour. Being aware that your actions may be broadcast to a wide audience who hold power to determine your tenure on the show, and to some extent, whether you are hated online, can make the contestants police their own behaviour. This affects the authentic, uncensored and unmoderated show of human behaviour that is usually expected from Reality TV. Could this denote a shift in reality shows from being ordinary and authentic to a more poised, unrealistic standard that society expects to see?

Shows like Love Island and Big Brother have begun to recruit more influencers and social media stars as contestants. Influencer careers are built on targeted impression management. To influencers, being on a reality show gives them the opportunity to build their brand and have a larger platform to make a splash in a growing industry with a wavering shelf life. Fashionable influencers, beautiful destinations, an almost endless supply of haute couture and cuisine? It almost looks like the producers of these shows are trying to make the fishbowl sound like paradise. Surely, it cannot be that bad. They are well-fed, dressed, and somewhat entertained. Does this not sound better than being chained to a wall, in rags, and with scraps to eat? Gilles Deleuze, a French philosopher, published a Postcript on the Societies of Control where he argues that society has moved from one of discipline to one of control. Power here takes on an invisible form and exercises control through incentives. The key is to normalise, if not glamorise the giving up of information while giving them the illusion of freedom.

Reality shows like Love Island, while being a blatant violation of privacy, does seem tolerable when we think that we can get paid for living a few months in luxury, all for the price of being watched. When one watches unrealistic unscripted shows, they might find themselves imagining how they would fare in the same situation. Apart from Reality TV, we see regular instances of normalising surveillance. In filling up forms for hospitals, or a random website. While using Google Maps during travel. Our social media itself is a representation of a more savoury version of our lives. An image purposefully manipulated and managed to look a certain way. Our search histories are used to deliver tailored content and adverts to our feeds. It almost feels like being watched is a privilege; like it somehow benefits you.

By exposing ourselves to this constant surveillance, there is an invisible, yet undeniable compulsion for self-regulation. While googling a website that could have vulgar misinterpretations in the wrong context, why do we find ourselves deleting it from search histories? With the rise of Work From Home as a norm, the act of being monitored in the home by your workplace has also been normalised. If staying home was truly liberating from the usual expectations of appearance, why have cosmetic surgery trends boomed during the pandemic? Did we really think that working on video call softwares that has a dedicated space constantly focusing on our own visage will not have any repercussions on how often we look and scrutinise ourselves? After being on reality shows, contestants (usually female) tend to get plastic surgery, usually as a result of possible bullying from the audience and rising insecurities. However, a new trend shows that contestants have started to get tweaked before entering the show in expectation of a perceived audience. Self-regulation and self-consciousness has pervaded many moments of our lives. From the urge to make everything picture-perfect and instagram-worthy, to deleting search histories, surveillance culture has grown to be quite powerful in this era of technology and digitisation. Is Big Brother actually watching? More importantly, have we begun to internalise and accept it?

Let us once again go back to the question posed at the beginning of this article. Does it look as simple as it did before? Does privacy look like an easy cost to bear for a million dollars? It has definitely made me stop and reconsider. Maybe I’ll still go for the money. My favourite influencer told me to keep grinding and hustling to get that coin one way or another. At this juncture, I would like to issue a special shoutout to Gossip Girl for satirising surveillance culture. I was young and ignorant when I chose to focus on the petty drama instead of the privacy infringement of minors that the show capitalised on. I shall also never look at Love Island or Big Brother the same way again. The shows eerily heralded the era of surveillance culture and invisible control that has come to become our reality.

Design by Abhiram V M