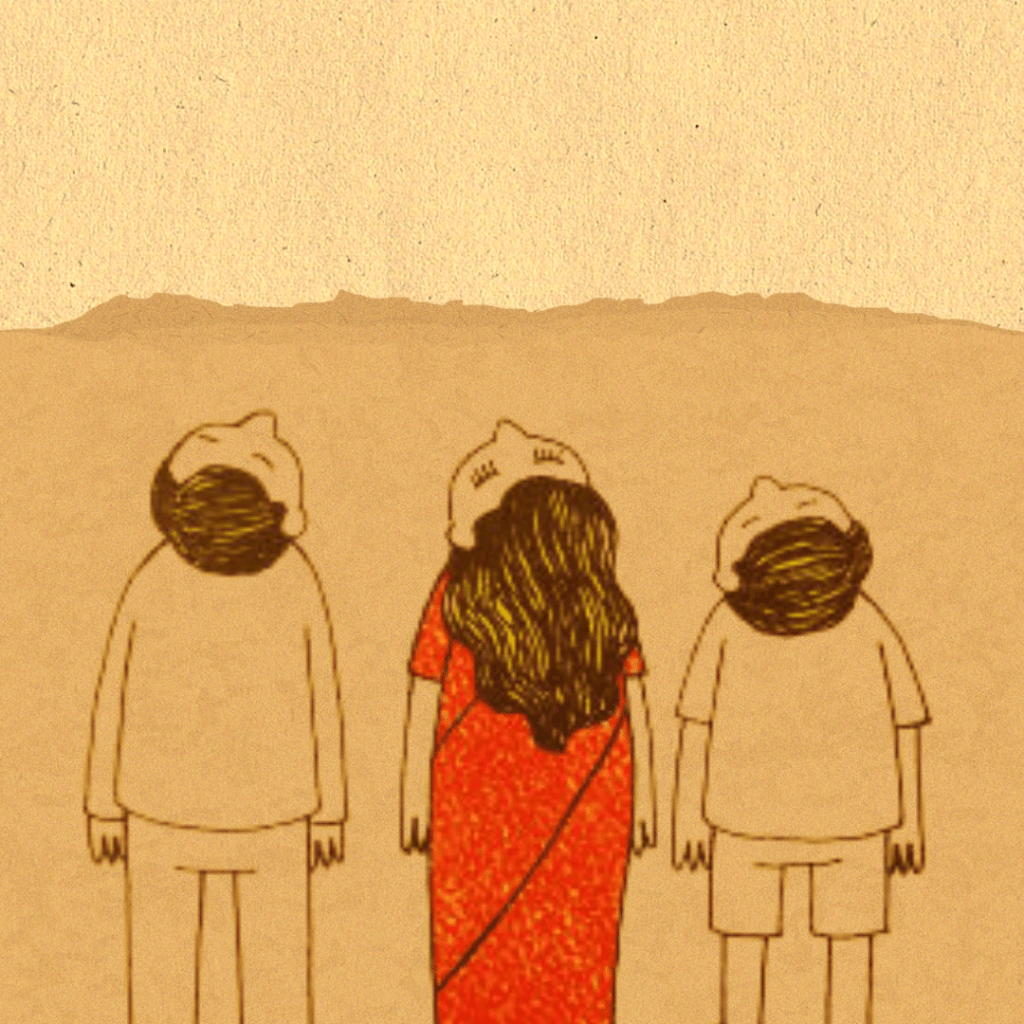

What makes a father ponder about his son’s life three years after his suicide? When Ousep Chacko finds the last cartoon his son drew, he restarts his journey for clues about Unni’s death. From this point, the story slowly unravels the life of Unni Chacko, a seventeen year old talented cartoonist who had jumped from the terrace of his building. Manu Joseph shows us how Unni’s death impacts his family, and Ousep’s questioning gives us a glimpse into what others saw in Unni. As the story progresses, we get a bigger picture and a better understanding of the brilliant boy who charmed everyone. But the question that remains till the very end is the central question of the novel. Why did Unni do what he did? Ousep is haunted by this as he goes about his daily life. Mariamma Chacko, Unni’s mother, believes that her son could not have died without leaving her a note. Thoma Chacko, Unni’s younger brother, grapples with the big shoes his brother left for him to fill, but somehow, he can never be like Unni.

The Illicit Happiness of Other People is set in the Madras of 1990. Already somewhat out of place as a Malayali Christian family among Tamil Brahmins, the Chackos stand out even more after Unni’s death. To be fair, Ousep’s drunken shouts every night from the main gate of Block A and Mariamma’s angry rants to the walls put them apart from every family even before that. Among the banker husbands who go to work on scooters, housewives, and sons who prepare for JEE, the Chacko family is quite the odd one out. Ousep is a journalist with a Best Writer Award and Mariamma has a postgraduate degree in economics. However, as Thoma says, the father is an alcoholic and mother is a nut; he is embarrassed of them. But Unni was not; Unni was never embarrassed of anything or scared of anyone. It is quite evident that Thoma looks up to his brother. As we go forward in the story, however, we are tempted to agree with Mythili – what an idiot, Unni, what an idiot.

Mythili Balasubramanian is the girl-next-door, who was thirteen years old when Unni died. She was like a daughter to Mariamma, and often spent her time playing with the brothers in the Chacko household. Now, she is a sixteen year old pretty girl – and Manu Joseph keeps reminding us of this when he describes the male gaze the women and girls in the novel are constantly subjected to. Everyone in Block A waits for Mythili to appear on the balcony – the older boys sitting on the wall and the younger boys playing cricket alike. There are boys walking on Balaji Lane just to get a glimpse of Mythili, straightening their shirts and flattening their hair when they see her. Joseph speaks about the inescapability from the male desire and the constant objectification of a woman’s body in the eyes of a man. This theme is a strong undercurrent throughout. Manu Joseph intertwines other important themes along with the main theme of understanding human life and the ‘truth’.

As the story progresses, Ousep continues hounding those closest to Unni, despite their reticence. When Ousep begins stalking some of Unni’s friends for answers, I became equally invested and even chalked up his borderline criminal behaviour to a father’s desperation. Through this we learn, along with Ousep, many puzzling things about Unni. Why did he tell everyone he knew a corpse? How could anyone know a corpse? Unni and his two closest friends in twelfth grade used to regularly visit a nun who took a vow to stay silent. And through his cartoons, we learn about Unni’s theories of the world. His cartoons usually do not have any dialogue, because Unni preferred to convey the story through pictures entirely. His cartoons also have a deeper meaning – sometimes they are satirical takes, sometimes they are theories about truth, humankind and the universe. Ousep also talks to the cartoonists Unni knew, to pry information about the son he barely knew. At home, Mariamma, Unni, and Thoma were a team and they knew how each other worked. Ousep gets to know his son properly only after his death.

The story is told in multiple points of view, which can go awry in the wrong hands, but Manu Joseph skillfully brings together each character’s perspective of Unni, slowly assembling all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. Unni remains a mystery until the very last piece falls in place, and this pulled me in as I continued to read the novel. It first seemed to me that the story revolved around Unni’s suicide. It most certainly does; but more important is Unni’s outlook towards life. His conception of the origin of human life. The ending is quite fitting, but at the same time, it left me quietly brooding for a while. Whether you see it coming or not, it is bound to leave you wondering about the role happiness plays in one’s life.

Unni’s theories are not just profound, sometimes they’re also hilarious, like this one time he talks to Mythili about a book he’s reading, a book about The Folly of Two. Folie à deux. Unni tells Mythili about the underground Union of Insulted French Syllables, and the revenge of the letter ‘x’, the most scorned letter in the French language, with the invention of the word ‘x-ray’. Unni also believes that delusions exist to be passed on to others; that’s how folie à deux works. Truth, he says, is a successful delusion. Why, then, did such a brilliant boy decide to die? When everyone tells Ousep that it was because his son was secretly depressed, and asks him to give up his questioning, he wonders why the world is so bent on proving the triumph of the normal over the unusual. And he wonders why Unni did what he did.

What an idiot, Unni, what an idiot.

Edited By S Santhosh Mohan