– Samyuktha Vijay

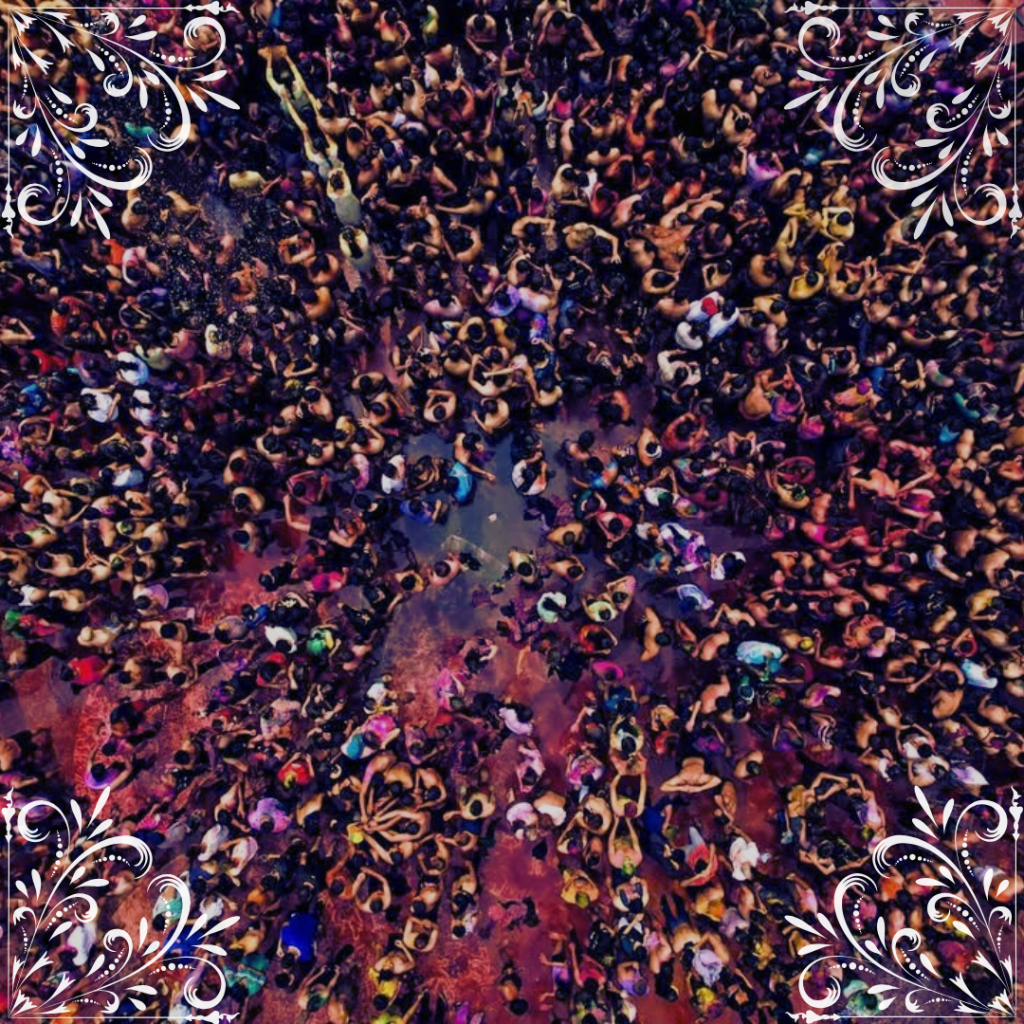

Holi at insti is an explosion of colour, energy, and unfiltered joy. Every year, the campus comes alive as the SGS sphere pulls out all stops to organize one of the grandest celebrations, complete with DJ sets, massive water tanks, and an astonishing 500 kilograms of colour powder. The Open Air Theatre transforms into a sea of exuberance as hundreds of students gather in the morning, ready to drench themselves in colour, dance to pulsating beats, and revel in the spirit of Holi. With its sheer scale and infectious enthusiasm, Insti Wali Holi rivals even the most extravagant city-wide celebrations, making it an unmissable highlight of the even semester. Yet, the experiences of countless female students year after year proves one thing: beneath this festive exterior lies a subtle choreography of gendered movement that mirrors broader societal patterns of space occupation and negotiation.

Before I get into my rant, I want to make one thing clear– women’s experiences in public spaces, especially in crowded venues like these, involve a constant negotiation of personal comfort, safety concerns, and deeply ingrained social norms that are starkly different from those of men. So, if anyone feels the urge to call this cribbing about a fun festival, take a moment to consider that my perspective might differ from yours simply because the space itself was not designed with me in mind. There is ample research on public spaces that demonstrate how socialized gender norms deeply influence the way men and women interact in and with public environments. A 2022 study published in Buildings noted that differential socialization plays a substantial role in how men and women learn to occupy space. Through this process, gender is a socially constructed phenomenon where families and educational systems guide children to acquire gender-typed behaviors. For women, this translates into being taught to take up less space, speak more softly, and generally maintain a smaller physical presence– behaviors that directly impact how they navigate crowded public venues. And at OAT, this gendered division of space becomes immediately apparent. The bowl area, ostensibly open and accessible to all, reveals a distinct pattern of occupation and movement. Male students, many shirtless and uninhibited, command the central spaces with confident exuberance. Their movements were expansive– running, jumping, even climbing onto the stage and freely traversing the grounds with little apparent concern for their physical impact on others. In stark contrast, all-female groups formed small defensive circles at the periphery, creating temporary sanctuaries amid the chaos.

One particularly telling finding comes from a 2017 social experiment which observed differences in the walking mannerisms of men and women on public sidewalks. When approaching someone walking in the opposite direction, women were more likely to move aside to let others pass, while men tended to “barrel forwards and assume that the other person will move”. This everyday interaction reveals a deeply embedded expectation that women should yield space to men. At our Holi celebration, this dynamic played out repeatedly– women’s circles dissolving and reforming elsewhere whenever male students pushed into their established spaces. As cultural analyst Sanjukta Basu puts it, women are allowed to venture out in public space, but not really own it. This statement encapsulates the core of the issue: despite having formal access to public spaces, women lack the social permission to fully inhabit and claim these spaces as their own.

All-female groups, including mine, exhibited a distinctive spatial hesitancy– constantly searching for that perfect equilibrium of visibility and safety. These groups methodically sought locations that were sufficiently populated to provide the anonymity of a crowd, yet not so dense as to risk unwanted physical contact with male revelers. This careful negotiation reflects what researchers have termed safety work–the additional mental and physical labour women perform to maintain personal security in public spaces.In contrast, mixed-gender groups moved with noticeably greater confidence and territorial stability. Research on public space occupation suggests that the presence of male allies functions as a form of social buffering, reducing the perceived need for hypervigilance. Women’s perception of risk decreases significantly when accompanied by trusted male companions, creating what the researchers call portable safe zones within otherwise concerning environments. Thus, women’s freedom of movement becomes contingent on male presence– a subtle reinforcement of dependency rather than true spatial equality.

During one particular moment, a male student carelessly tossed an empty water can after emptying its contents, which landed heavily on my friend. Rather than confronting this intrusion, we silently relocated to a less crowded area. This response wasn’t unique– it was a calculated decision that reflects the additional cognitive load women carry in public settings. A 2024 study published in Gender & Development observes that the public-space body is one that for women is largely marked by erasure, a concept that materialized before my eyes as we voluntarily erased our presence from one space to reestablish it elsewhere. A physical encounter during my first year was emblematic of these dynamics. Knocked down by a running male student with such force that I sprained my knee, I was struck not only by the physical impact but by the casualness with which he barely paused to acknowledge the harm before continuing his celebration. This moment crystallized the asymmetry in our experiences– my body becoming an obstacle in his path rather than an equal participant with claim to space. Conversations with fellow female students reveal similar stories– tales of being jostled, splashed without consent, or forced to repeatedly relocate throughout the celebration. These aren’t isolated incidents but rather manifestations of what feminist geographers term the geography of women’s fear. Research on women’s navigation of the Delhi Metro system suggests that fear of violence leads to a restriction of women’s mobility and their sense of embodiment in public space. At Holi, this restriction manifested not through complete avoidance but through constant, vigilant adjustment.

By questioning these dynamics, I’m not trying to diminish the significance of Holi or to suggest abandoning the celebration altogether. Rather, I’m merely reflecting on how even our most joyous communal experiences remain shaped by gendered expectations about movement, space, and physical presence. The willingness of female students to adjust rather than assert shows that Holi at insti needs to be viewed as a microcosm of larger social dynamics, where a female student’s participation remains contingent on their willingness to accommodate male spatial dominance. Our collective hesitation before attending, despite genuine excitement for the festival, speaks to the anticipatory calculation that becomes second nature.

What remains most striking is the unquestioned acceptance of these patterns. The male students running unchecked, claiming space with their bodies, likely never consider their movements as acts of spatial dominance. Meanwhile, female students’ constant recalibrations– forming protective circles, yielding space when approached, relocating after uncomfortable encounters– are performed with such practiced smoothness that they become nearly invisible, a choreography so familiar it escapes conscious notice.

Amidst insti’s grand celebration of colour and community, the subtle shades of gender politics emerge, mirroring the dynamics that shape our everyday movements. The festival grounds are more than just a riot of vivid hues; they reflect the lingering, persistent patterns of a society still learning to create truly equal access to public joy and celebration.

___________________________________________________

Design by Neenu Elza