— Roshni

This article is Part 2 of a two-part series. You can read Part 1 here.

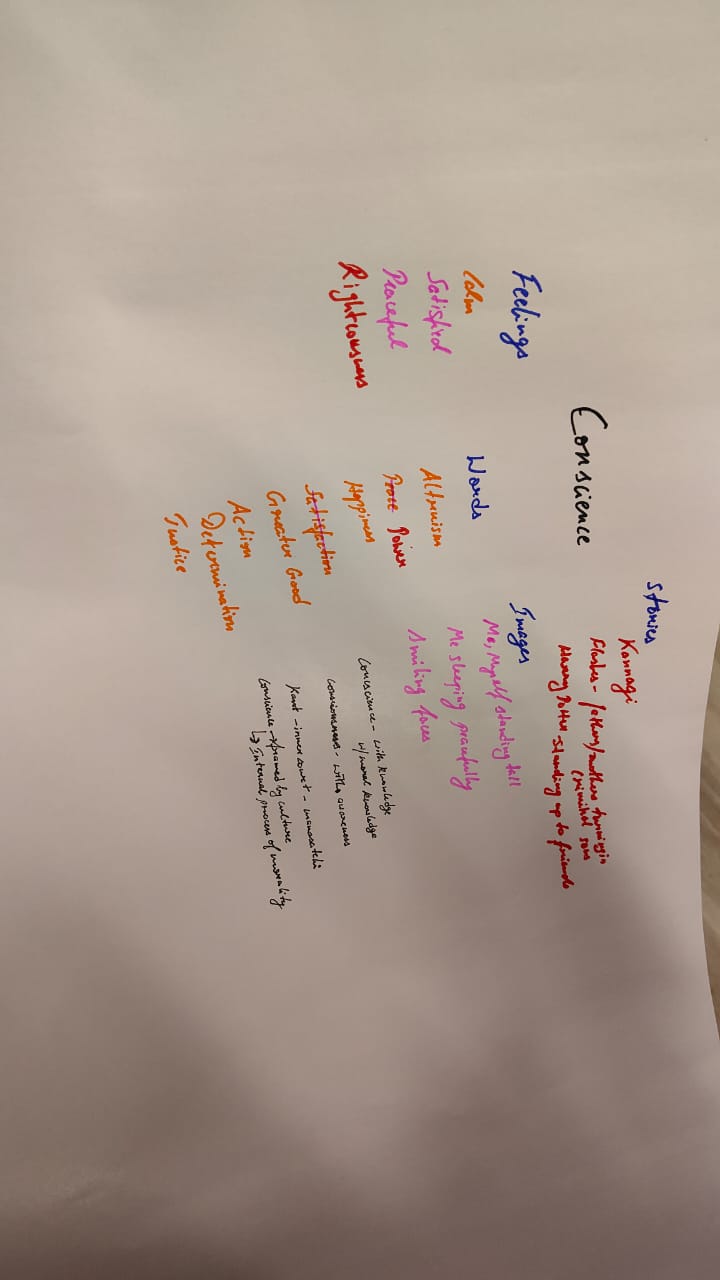

What is conscience to you? The walls of Mahatma Hall resounded with the clatter of sketch pens on chart paper for a deceptively innocent activity that required us to meet morality in the mirror. Scattered thoughts and callously drawn arrows painted mosaics of conscience: the words, feelings and images ‘conscience’ evoked and the stories we associated with it.

In Tamil, conscience is termed manasaatchi, which roughly translates to manam ‘the heart/mind’ as saatchi ‘the witness.’ An invisible observer that sees all, conscience stimulates the image of a Foucauldian Panopticon. We associate it with God and religion, with notions such as ‘The Judgement Day’ or karma looming large in our minds. Simply put, conscience is who you fundamentally are. It entails aspects of you that you wouldn’t compromise on, and as such, drives empirical decision-making. It reflects beliefs you’d stand up for, even in the face of adversity, or succumb to, suffering the perturbing whiplash of a guilty conscience.

Acting conscientiously brings with it a gift bag of liberty that screams, ‘I did the right thing!’ Au contraire, conscience feels uptight. It feels like a knotted stomach, anxious pangs in the heart, persevering self-doubt, shame and guilt. Do we feel the censure of a bad conscience more than the applause of a good conscience? For most of us, the answer is yes. Nevertheless, we want to hold on to conscience because a ‘bad conscience’ is outweighed by its ‘good Samaritan’ cousin that espouses a shared sense of trust and goodwill, bolstering blocks of fraternity through the extolled virtues of kindness and humanitarianism. It is the soul-force that wags its fingers at us with threats of repercussions but never fails to nurture empathy, or at least sympathy, fuelling harmony in the interest of the greater good.

As for tales of conscience, my peers drew from religious epics and Shakespearean literature to discuss characters who underwent turmoil due to a crisis in conscience: Dasharatha and Karna from the Mahabharata, Rama’s moral dilemma when he had to subject Sita to trial by fire, and Hamlet’s infamous monologue ‘To be or not to be!’ Fantasy epics such as ‘Game of Thrones’ stand tall in pop culture due to their honest portrayal of morally grey characters. The story of ‘The honest woodcutter’, who chooses his iron axe over golden and silver axes and is rewarded with all three by the goddess, was retold. ‘Kite Runner’ was next mentioned, as it portrayed a breach of conscience which haunted a friend all the way into adulthood. From fairy tales to most movie plots, society reinforces that morality is rewarded and an immoral antagonist is scorned, shunned and deserving of punishment. I wondered why no one brought up stories where the bad guy was rewarded, where acting without a moral compass meant no consequence. Life was unfair, after all.

Do we dare to dream of a world that rids itself of conscience? We all echoed ‘No’ in unison. Conscience is tied to feeling humane, and therefore is a fundamental aspect of feeling human. It is the inner voice that helps us think critically and challenge ourselves, and teaches us to narrativise life. It is both within us and detached from us, constituting the ‘transcendental self.’ As we left our private corners to exchange maps of conscience with one another, Mr Tikoo encouraged us to pursue conscience as a path to discover the values within ourselves and in each other, as opposed to relegating it to the realm of rigid moral discourse of right and wrong.

And now that you, the reader, have been equipped with the knowledge of all things conscience, it is time for you to ponder on the feelings, stories, and images that would paint your personal wall of conscience. You just might discover the hidden voice of your heart. And we end by circling back to the beginning: What is conscience to you?

—Design by Vasuki