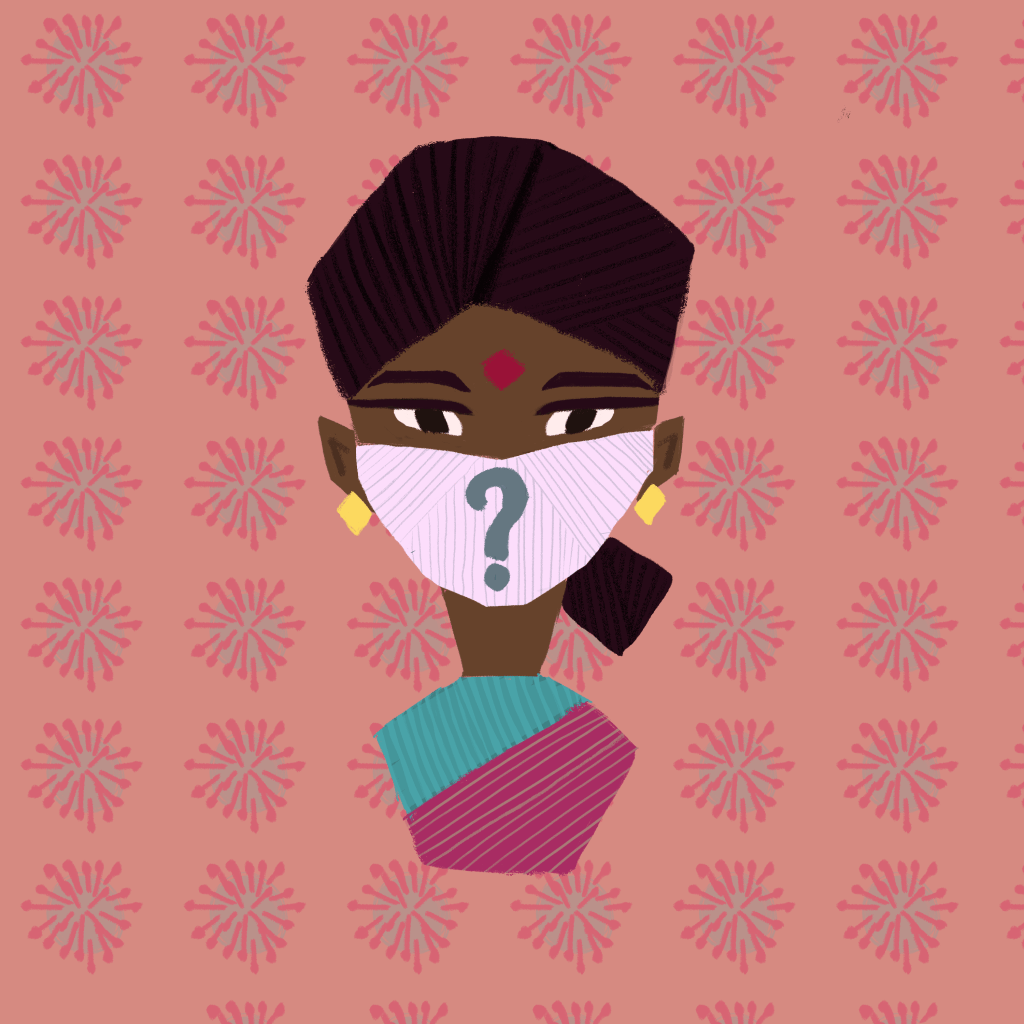

The COVID-19 pandemic has foregrounded social inequalities along the lines of gender, caste and class. In this article, B Nandhiga Ramani looks at the COVID-19 pandemic through a gendered lens.

The rapid spread of COVID-19 has highlighted the critical role of care work, particularly in times of crisis. The lockdown initiated to contain the spread of the pandemic has resulted in the closure of many services—including schools, basic health care, and daycare centres—shifting their provisioning to households. Traditionally, it is women who are perceived to be responsible for the physical and emotional work of caregiving. The lockdown may have led male family members to realise the effort that goes into household work, but their participation is still limited by their choice and patriarchal norms. Women, on the other hand, lack the choice to abandon doing household work as they are conditioned to tie their self-worth to how well they perform their traditional caregiving roles. To shape them as such, they are made to internalize qualities like care, empathy, kindness, and patience from childhood.

The norm of women being caregivers was justified as part of the division of labour put forth by the capitalist mode of production with the advent of industrialisation. While men went out and earned for the family, women stayed in and took care of the house. However, the status quo has been slowly changing with more women going out to work. Furthermore, with the lockdown, men are also staying inside the house more often. Yet, more often than not, women remain the primary caregivers. Especially for working women, this is an added responsibility, as they have to take care of their jobs and the household simultaneously. The temporary halt of caregiving services like maids and childcare services has further increased the burden of work.

Women are at the forefront of fighting the pandemic as they make up more than 70 percent of workers in the health and social sectors. These healthcare workers have dual responsibilities—not only do they spend long hours on providing health services, they also perform much of the increasing care work in the household. They are also at a higher risk of infection, particularly those in jobs that lack protective gear and protocols to keep them safe. Though women frontline workers are paid for the care work they provide, they occupy lower positions in the organisational hierarchy. Thus, the value of the service they provide is significantly lower even when it is essential.

Though the less visible parts of the care economy are coming under increasing strain due to the increased demand for care work, they still remain unaccounted for in the economic response. The failure of states to deliver gender-responsive public services like education, health, transport, water and sanitation, and early childcare is an added burden. The pandemic has given us an opportunity to re-evaluate the value of the care work provided by women. Unpaid care work is the hidden engine that keeps the wheels of our economies, businesses, and societies turning. Immediate action is thus needed to guarantee continuity of care for those who need it and to recognize unpaid family and community caregivers as essential workers in this crisis.

While women’s work at homes still remains unrecognised, an interesting trend of women-led nations and women leaders doing well in handling the pandemic has emerged. Countries like New Zealand, Norway, Taiwan, and Iceland have been commended for their outstanding way of handling the crisis. Closer home, Kerala’s Minister of Health and Social Welfare KK Shailaja has been applauded widely for her effective handling of the virus. Most of these leaders have contained the pandemic through early scientific intervention, widespread testing, easy access to quality medical treatment, aggressive contact tracing and tough restrictions on social gatherings.

This trend has been analysed in detail by many experts and talked about by leading newspapers. They point out that the primary reason why women-led nations are performing well is due to the “feminine qualities” that these leaders and their countries have adopted and applied in their policies. These feminine qualities include being “compassionate, courageous, data-based, decisive, and kind” and also being “calm, caring, clear, empathetic, honest, science-driven, and transparent”. An article published in Forbes says that “the empathy and care which all of these female leaders have communicated seems to come from an alternate universe than the one we have gotten used to. It’s like their arms are coming out of their videos to hold you close in a heart-felt and loving embrace. Who knew leaders could sound like this? Now we do.”

A point that these experts miss is the structural reasons that have allowed for the stereotype of feminine qualities to survive. As Simon de Beauvoir has famously said, “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Similarly, women are not born with these “feminine qualities” but rather internalise them throughout their lives. Judith Butler’s performative theory of gender addresses this issue when it says that gender is performative—that is, performances of women are compelled and enforced by historical social practices. This is to maintain and legitimize a seemingly natural gender binary. Women are told to be kind, empathetic, caring and emotional from childhood to adhere to their traditional patriarchal role of the caretaker of the household.

The discourse around female-led nations having these feminine qualities leading to the adept handling of the virus reiterates this gender binary. It reinforces the belief that women are born with these feminine qualities and it is natural that they are exhibiting them. In the past, many business houses had said that gender inclusivity is important as feminine qualities will help bring in profits. At the surface level, one can celebrate this as this means greater inclusion of women in workspaces and the recognition and promotion of feminine qualities in public spaces. However, this hides the phallocentric logic that it revolves around. Patriarchy celebrates these qualities and allows for women in workspaces only when it suits its need for higher profit-making. In the case of this pandemic, it subtly creates the belief that women are better leaders only when it comes to emergencies which require care work.

The dualism of the public/private binary carries gendered connotations, in that the public holds more value than the private. We have noticed how the same feminine qualities that are frowned upon inside the home are now being heralded among world leaders. Similarly, women’s work has been recognised in the public policy-making arena, but not in domestic households or as community healthcare workers. The record of women-led nations doing well during this pandemic will only strengthen the fact that more women are needed in higher-decision making bodies. Yet, this should be ensured without upholding the gender binary of male/female or masculine/feminine, as it only re-establishes the patriarchal norms that feminism is working to abolish.

Edited by Swathi C S

References

Butler, Judith. 1988. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal Vol. 40, No. 4: 519-31.

Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas. 2020. “Are Women Better At Managing The Covid19 Pandemic?”. Forbes April 10, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomaspremuzic/20/04/10/are-female-leaders-better-at-managing-the-covid19-pandemic/#1029518528d4

Champoux-Paillé, Louise and Croteau, Anne-Marie. 2020. “Why women leaders are doing better than men in fighting the coronavirus pandemic.” Scroll, May 17, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://scroll.in/article/962057/why-women-leaders-are-doing-better-than-men-in-fighting-the-coronavirus-pandemic

Fincher, Leta Hong. 2020. “Women leaders are doing a disproportionately great job at handling the pandemic. So why aren’t there more of them?” CNN, April 16, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/14/asia/women-government-leaders-coronavirus-hnk-intl/index.html

Hassan, Jennifer and O’Grady, Siobhán. 2020. “Female world leaders hailed as voices of reason amid the coronavirus chaos.” The Washington Post, April 20, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/04/20/female-world-leaders-hailed-voices-reason-amid-coronavirus-chaos/

Huang, Peter H. 2020. “Put More Women in Charge and Other Leadership Lessons from COVID-19.” U of Colorado Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 20-21: 1-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3604783

Hughes, Christina. 2002. Key Concepts in Feminist Theory and Research. London: SAGE Publications

India Development Review. 2020. “Sexism In Economy: Women’s Unpaid Care Work Is Still Not Acknowledged Or Paid.” Feminism in India, February 13, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://feminisminindia.com/2020/02/13/sexism-economy-womens-unpaid-care-work-not-acknowledged-paid/

Inter-Parliamentary Union. 2020. “In 2020, world “cannot afford” so few women in power.” March 10, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.ipu.org/news/press-releases/2020-03/in-2020-world-cannot-afford-so-few-women-in-power#_ftn1

Nesbitt-Ahmed, Zahrah and Subrahmanian, Ramya. 2020. “Caring in the time of COVID-19: Gender, unpaid care work and social protection.” UNICEF Blogs, April 23, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://blogs.unicef.org/evidence-for-action/caring-in-the-time-of-covid-19-gender-unpaid-care-work-and-social-protection/

Reuters. 2015. “Indian Women Do 10 Times As Much Unpaid Work As Men: McKinsey.” Huffington Post, November 4, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.huffingtonpost.in/2015/11/04/indian-women-economy_n_8469456.html

Shah, Sana. 2020. “Remembering The Wages For Housework Movement During This Lockdown.” Feminism in India, May 8, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://feminisminindia.com/2020/05/08/remembering-wages-for-housework-movement-lockdown/

Singh, Asavari. 2020. “What Does It Take To Get Indian Men To Do Household Chores?” Huffington Post, April 12, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/what-does-it-take-to-get-indian-men-to-do-household-chores_in_5e920a5cc5b6f7b1ea82b7a2

Smith, Nicole. 2020. “6 Leadership Qualities Displayed by Women World Leaders During COVID-19.” Sway, May 19, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.swaay.com/global-women-leaders-covid-19

UN Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women. 2020

Wittenberg-Cox, Avivah. 2020. “What Do Countries With The Best Coronavirus Responses Have In Common? Women Leaders.” Forbes, April 13, 2020. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/avivahwittenbergcox/2020/04/13/what-do-countries-with-the-best-coronavirus-reponses-have-in-common-women-leaders/#7b047d83dec4